| Text |

In

light of the success of the statin drugs, interest in preventive cardiology

has shifted to new frontiers of pharmacologic intervention: defining optimal

levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, inhibiting cholesterol

absorption, addressing the inflammatory component of atherosclerosis,

and increasing the levels of protective high-density lipoprotein (HDL)

cholesterol. This last approach attracted attention last year when it

was reported that a new drug, torcetrapib, could substantially increase

levels of HDL cholesterol by inhibiting cholesteryl ester transfer protein.(1)

The drug was heralded as a novel weapon against heart disease that could

be an important clinical tool if its effect on lipids actually reduces

the rate of clinical events. Subsequent studies reported in March confirmed

the drug's capacity to increase HDL cholesterol markedly.(2) Pfizer, which

holds the patent on torcetrapib, is launching several studies to assess

the clinical outcomes of treatment with the drug. One study, scheduled

to be completed next year, will evaluate the drug's effect on atherosclerotic

plaque, as measured by intravascular ultrasonography. In a second trial,

investigators will study 13,000 patients over a period of five years to

measure rates of myocardial infarction and stroke.

Enthusiasm about this potentially important new therapeutic tool has been

tempered by concern about how the company will study and market the drug.

Pfizer's trials will study torcetrapib only in combination with the company's

widely used atorvastatin (Lipitor), the best-selling drug in the world

Total Pfizer

Revenues from Lipitor, 1999–2005.

The figure for 2005 is extrapolated from first-quarter revenues. Data

are from Pfizer.

Sales

of Lipitor account for about half of Pfizer's annual profits; the company's

patent is due to expire in 2010. Because of this study design, the Food

and Drug Administration (FDA) will be presented only with data on the

torcetrapib–Lipitor combination as compared with Lipitor alone. If

the studies show that the combination is more effective than statin monotherapy,

the FDA is likely to approve torcetrapib for use only in a combination

product that includes Lipitor — not for separate use or use with

another company's statin or with a generic statin — because the only

efficacy trial data presented to it will be based on the combination tablet.

Such approval would make it impossible for physicians to prescribe the

new agent with any other statin — or even with generic atorvastatin

when it becomes available in five years.

Normally, antitrust laws would prohibit a manufacturer from offering a

drug only when "bundled" with another one of its products. It

appears that Pfizer will avoid such antitrust prohibitions by having the

FDA do its bundling for it. The FDA's acceptance of the proposed trial

designs in effect acknowledges that since the new drug is Pfizer's intellectual

property, the company's research plans are subject only to its own corporate

prerogative. These studies will enroll thousands of patients who are at

risk for cardiovascular disease, cost Pfizer millions of dollars, and

go on for years. But when they are completed, clinicians, patients, payers,

and regulators will still not know how well this important new approach

to atherosclerosis performs in combination with any risk-modifying approaches

other than Lipitor. Pfizer's position is that it invested in the development

of torcetrapib and is paying for its evaluation, so it can study and market

the resulting product however it sees fit. As with other costly new drugs,

however, research leading to the product's development was also supported

by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).(1,3)

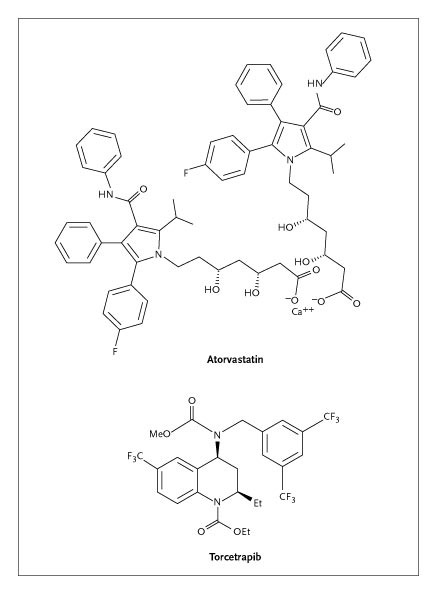

Molecular Structure

of Atorvastatin and Torcetrapib.

High cost will be the most prominent downside of the FDA-sanctioned yoking

of the two brand-name drugs. But there will be clinical problems as well:

patients who cannot tolerate (or afford) Lipitor will have no way of obtaining

torcetrapib for use with another statin that may be better for them. Physicians

who want to raise a patient's level of HDL cholesterol — but who

do not want to be forced to use Lipitor — will not have access to

torcetrapib.

Other research options would have been feasible. Although it makes sense

initially to test the additive effects of torcetrapib plus statins over

statins alone, a target level of LDL cholesterol could have been set for

the trial, with study participants randomly assigned to receive one of

several statins — a design that would have produced more generalizable

findings. In another scenario, participating clinicians could have reached

a target LDL level using the statin of their choice, with patients randomly

assigned to receive either torcetrapib or placebo in addition. The FDA

often discusses the design of preapproval studies with manufacturers and

could have tried to convince Pfizer to implement a study design geared

toward better protection of the interests of science, patients, and even

payers. But if such discussions took place, they did not succeed. This

may have been the result of the FDA's fear of litigation by the manufacturer,

since the owner of a new drug has the legal (although perhaps not the

moral) right to conduct its preapproval clinical studies as it sees fit.

The next test for the FDA will come in its response to the results of

these trials. What if the combination therapy does reduce the rate of

cardiovascular events or atherosclerotic progression better than atorvastatin

monotherapy? In principle, the FDA could approve torcetrapib for use in

combination with Lipitor, as a single agent for use with other statins,

or even alone in uncommon situations. But Pfizer is likely to request

approval only for the fixed combination, arguing that this is the sole

use of torcetrapib for which adequate trial data are available. The FDA

would have to muster uncharacteristic regulatory courage to persuade the

company to market the new drug in more than one form; the agency is unlikely

to do so and may lack the legal authority. Even if the FDA took such a

stand, it could find its options limited by the design of the preapproval

research. And in the end, whatever the FDA decided and regardless of the

role of public funds in the early development and evaluation of inhibition

of cholesteryl ester transfer protein to raise HDL cholesterol, Pfizer,

as the owner of the new compound, could still choose to make it available

only in combination with Lipitor.

The torcetrapib controversy brings several long-standing questions about

clinical drug research into sharp focus. In the 1990s, as pharmaceutical

companies became the most profitable industry group in the nation, their

annual research expenditures began to exceed the entire budget of the

NIH. Those profits and expenditures did not result in an impressive increase

in the rate of discovery of important new drugs by most of the large firms,

raising troubling questions about the supposed link between huge cash

flows and genuine innovation. Nonetheless, these shifting economic realities

helped entrench the dominance of pharmaceutical companies over the research

agenda for therapeutics. Growing deficits in the federal budget now place

considerable pressure on publicly funded medical research, which will

further limit the ability and willingness of the NIH to support applied

studies of drug efficacy and safety in the future. Thus, the scientific

questions that are asked in both domains will increasingly be defined

by the pharmaceutical industry.(4)

The torcetrapib–Lipitor bundling studies illustrate where this trend

can lead. The current trial designs may not optimally meet the scientific

needs of prescribers, the clinical needs of patients, the economic needs

of payers, or the regulatory needs of policymakers. But they superbly

meet the business needs of the sponsor — to create new knowledge

in a way that will protect the market share of the largest drug company's

most important product. A more science-based or patient-centered research

design would not have accomplished this goal as well; indeed, any Pfizer

official who signed off on such a study might be accused of compromising

his or her fiduciary responsibility to the company's shareholders.

This is the predictable consequence of an industry-driven approach to

defining the nation's drug-research agenda. But another vision is possible,

and it would reduce rather than increase public expenditures. Well-targeted

federally funded medication trials can more than pay for themselves; examples

to date include NIH-supported studies of estrogen replacement and of medications

for hypertension, which provided important insights into the risks, benefits,

and optimal use of these therapies. These needed insights can improve

care and save the nation billions in drug expenditures.(5) For instance,

if a moderate-size NIH-funded clinical trial of the cardiovascular risks

of coxibs had been performed in 2000 and 2001, most of the $2.5 billion

per year — about $1 billion annually from public coffers — that

was spent on rofecoxib (Vioxx) might have been saved. Other clinical examples

abound.

The torcetrapib story suggests that we have become too dependent on manufacturers

as the predominant source of our scientific knowledge about the effects

of medications. As Medicare prepares for an increasingly unaffordable

drug benefit, the best way to contain that public expenditure will be

to commit a small fraction of those funds to support such public-interest

drug trials, fairly comparing competing therapies (especially costly new

ones) with clinically realistic alternatives. With pharmaceutical costs

increasing faster than most other health care expenditures, the nation

requires studies that will meet the needs of evidence-based prescribing

and not just the needs of the pharmaceutical industry. It is not a question

of whether we can afford to pay for our own drug trials; it is increasingly

evident that we cannot afford not to do so.

Source

Information Dr. Avorn is a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School

and chief of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics

at Brigham and Women's Hospital — both in Boston.

References

1) Brousseau ME, Schaefer EJ, Wolfe ML, et al. Effects of an inhibitor

of cholesteryl ester transfer protein on HDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med

2004;350:1505-1515.

2) Davidson M, McKenney J, Revkin J, Shear C. Efficacy and safety of a

novel cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor torcetrapib when administered

with and without atorvastatin to subjects with a low level of high-density

lipoprotein cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:Suppl 1:394A-394A.

3) Brousseau MF, Diffenderfer MR, Millar JS, et al. Effects of cholesteryl

ester transfer protein inhibition on high-density lipoprotein subspecies,

apolipoprotein A-I metabolism, and fecal sterol excretion. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:1057-1064.

4) Avorn J. Powerful medicines: the benefits, risks, and costs of prescription

drugs. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

5) Fischer MA, Avorn J. Economic implications of evidence-based prescribing

for hypertension: can better care cost less? JAMA 2004;291:1850-1856.

|