| Text |

These

are trying times for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Worrying

data about the drugs they regularly use keep emerging. In September 2004

rofecoxib (Vioxx) was withdrawn by Merck after the adenomatous polyp prevention

on Vioxx (APPROVe)(1) trial showed an increase in major cardiovascular

events in patients with a history of colorectal adenomas who were randomised

to receive Vioxx, compared with those in the placebo group.w1 Rofecoxib

had been marketed as the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)

of choice because selective inhibition of the isoform 2 of the cyclooxygenase

(COX 2) enzyme made it highly effective but free from gastrointestinal

toxicity.

More unwelcome data from placebo controlled trials of rofecoxib's competitors

followed: valdecoxib (Bextra, Pfizer) taken after coronary artery bypass

grafting was shown to be associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular

events(2); and the adenoma prevention with celecoxib (APC) trial(3) reported

an increased risk of cardiovascular events associated with use of celecoxib

(Celebrex, Pfizer), a drug known to be less selective for COX 2 than rofecoxib

or valdecoxib.(4) A small increase in the risk of myocardial infarction

was also observed for the highly selective lumiracoxib (Prexige, Novartis).(5)

No data on the cardiovascular safety of etoricoxib (Arcoxia, MSD) from

large trials have been published so far, but no news is no longer good

news: patients and doctors are anxious to know whether cardiotoxicity

is a class effect applicable to any COX 2 inhibitor, or even to NSAIDs

in general.

In this week's BMJ two observational studies address this question. A

retrospective cohort study (BMJ_2005_330_1370)(6)

in patients with congestive heart failure found lower mortality in patients

treated with celecoxib than with rofecoxib or traditional NSAIDs. A case-control

study nested in a UK general practice database (BMJ_2005_330_1366)(7)

found a similar risk of myocardial infarction for celecoxib, rofecoxib,

ibuprofen and naproxen, but a somewhat higher risk with diclofenac.

We believe that these results should be interpreted with caution. For

example, the similar risk of myocardial infarction for naproxen and rofecoxib

found in the case-control study(7) is incompatible with the trial data(8)

and could be explained by confounding by indication if patients with a

history of heart disease were more likely to receive naproxen than rofecoxib

or other NSAIDs. The quality of the data on cardiovascular risk factors

and other potential confounders was poor in both studies, and the ability

to control for confounding therefore limited. For example, information

on smoking was unrecorded in 13% of cases and 20% of controls in the case-control

study(7) and entirely unavailable in the retrospective cohort study.(6)

What are the alternatives? We have argued that all unbiased data on serious

adverse events from clinical trials should be made available to independent

researchers and the public and analysed in a timely fashion.(9) Indeed,

in the case of rofecoxib, cumulative meta-analysis of clinical trial data

showed that an increased risk of myocardial infarction was evident from

2000 onwards.(8) Similar analyses are now required for the other COX 2

inhibitors.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other licensing authorities

are an important source of relevant data. The FDA reviews clinical trials

worldwide before approval and labelling, and again before relabelling

of approved drugs. As part of the 1966 Freedom of Information Act, the

agency is required to make available its reports on all drugs that are

approved. Unfortunately, these reports are not as useful as they could

be. We found that the criteria for including trials in reports were often

unclear. For example, only 16 out of at least 27 trials of celecoxib that

were performed up to 2002 in patients with musculoskeletal pain were included

in the relevant reports. In any event, reporting on study characteristics

and adverse events was not always transparent, and complete data on cardiovascular

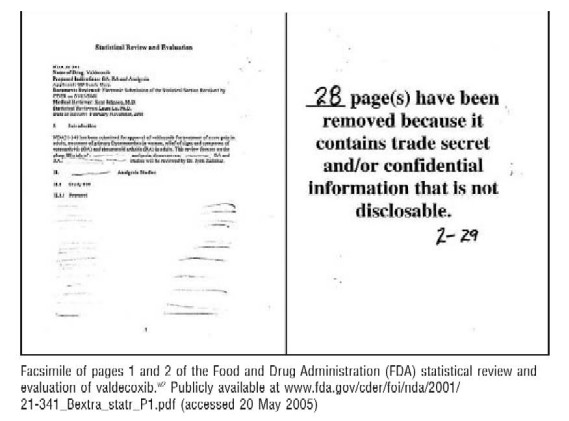

safety were available for only three trials. In the case of valdecoxib,

we found that many pages and paragraphs had been deleted because they

contained "trade secret and/or confidential information that is not

disclosable" (figure).w2

Facsimile

of pages 1 and 2 of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) statistical

review and evaluation of valdecoxib.w2 Publicly available at

www.fda.gov/cder/foi/nda/2001/21-341_Bextra_statr_P1.pdf

Surely,

the protection of the public's health justifies full access to the safety

data submitted by industry to the FDA and other drug licensing authorities,

and mandates transparent reporting on harms, in accordance with international

guidelines.(10) Meta-analyses of adverse events might not resolve controversies,

but will help decision making about issues such as the need for additional

trials.

Observational

studies "simply cannot test definitely whether there are small to

moderate risks or benefits of a class of drugs when the factors associated

with prescription of a particular drug are difficult to control and perhaps

even uncontrollable."(11) This statement referred to postulated adverse

events of calcium antagonists in the treatment of hypertension, a controversy

finally resolved by large pragmatic trials, including the seminal antihypertensive

and lipid lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT).(12)

Such large trials might be required, ultimately, to establish the best

and safest treatment for patients with musculoskeletal pain.

Peter

Jüni, Stephan Reichenbach, Matthias Egger

References

1) Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, Bolognese JA, Oxenius B, Horgan K,

et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal

adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 2005;352: 1092-102.

2) Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT, Langford RM, Hoeft A, Parlow JL,

et al. Complications of the COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib

after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2005;352: 1081-91.

3) Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Wittes J, Fowler R, Finn P, et

al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial

for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med 2005;352: 1071-80.

4) Warner TD, Mitchell JA. Cyclooxygenases: new forms, new inhibitors,

and lessons from the clinic. Faseb J 2004;18: 790-804.

5) Farkouh ME, Kirshner H, Harrington RA, Ruland S, Verheugt FW, Schnitzer

TJ, et al. Comparison of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen in the

Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET),

cardiovascular outcomes: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:

675-84.

6) Hudson M, Richard H, Pilote L. Differences in outcomes of patients

with congestive heart failure prescribed celecoxib, rofecoxib, or non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs: population based study. BMJ 2005;300: 1370-3.

7) Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients

taking cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs: population based nested case-control analysis. BMJ 2005;300: 1366-9.

8) Jüni P, Nartey L, Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Dieppe PA, Egger M.

Risk of cardiovascular events and rofecoxib: cumulative meta-analysis.

Lancet 2004;364: 2021-9.

9) Dieppe PA, Ebrahim S, Martin RM, Jüni P. Lessons from the withdrawal

of rofecoxib. Patients would be safer if drug companies disclosed adverse

events before licensing. BMJ 2004;329: 867-8.

10) Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gotzsche PC, O'Neill RT, Altman DG, Schulz

K, et al. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension

of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med 2004;141: 781-8

11) Buring JE, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH. Calcium channel blockers and myocardial

infarction. A hypothesis formulated but not yet tested. JAMA 1995;274:

654-5

12) Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the antihypertensive

and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT). JAMA

2002;288: 2981-97

|